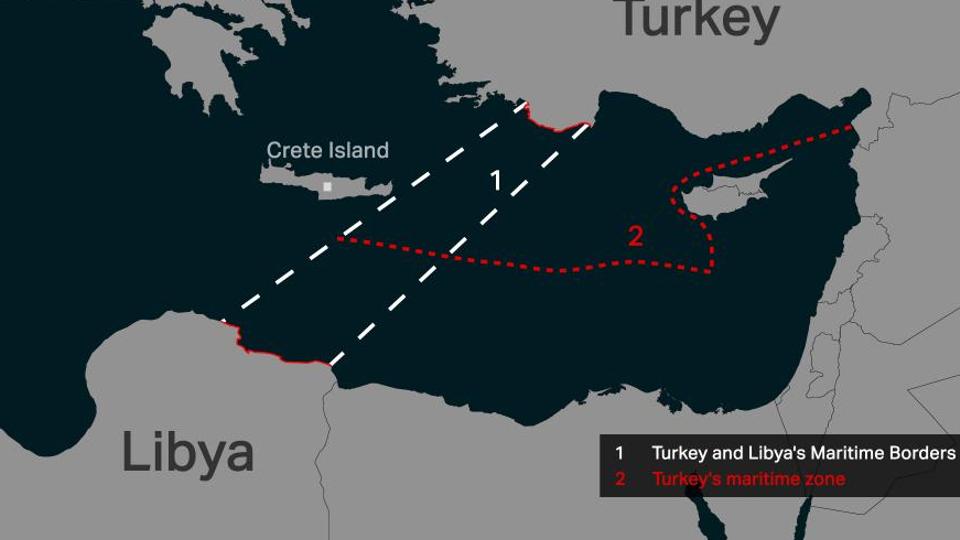

Turkey’s deal with Libya’s UN-recognised government in Tripoli is a signal to other Mediterranean states that Ankara can block their gas routes.

Turkey’s recent moves in the Eastern Mediterranean have made waves after it signed a maritime deal with Libya’s Government of National Accord (GNA) based in Tripoli. The deal is a clear signal to other coastal states in the region that the gas game will not be played without Ankara’s consent.

Greece, Egypt, Israel and the Greek Cypriot Administration (GCA) have previously signed maritime agreements, excluding Turkey, to draw up their respective Exclusive Economic Zones (EEZ) in the Eastern Mediterranean and launching their own exploration efforts.

“Other international actors cannot conduct exploration activities in the areas marked in the [Turkish-Libyan] memorandum. Greek Cypriots, Egypt, Greece and Israel cannot establish a natural gas transmission line without Turkey’s consent,” Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan said, referring to the Ankara-Tripoli deal.

Before the Turkish-Libyan maritime deal, Greece, Israel and the GCA were trying to outmanoeuvre Ankara by designating their own EEZs, signing agreements among themselves.

Furthermore, the three Mediterranean powers have established a consortium, through which they have developed the EastMed pipeline project, aiming to transport the newly discovered gas reserves from the Eastern Mediterranean to southern Europe.

While the route of the pipeline goes through Turkey’s EEZs, Ankara was not consulted on the implementation of the project, angering the Turkish state, which eventually developed its own plan to block the EastMed project by reaching an understanding with Libya’s UN-recognised Tripoli government.

Turkey does not recognise the agreements because Ankara believes the Greek Cypriot Administration does not represent all the inhabitants of the island.

Since 1974, Cyprus has had two divided administrations – one led by Turkish Cypriots in the north part of the island and another led by Greek Cypriots in the south part of the island.

In Cyprus, located in the middle of the Eastern Mediterranean, the island’s Turkish and Greek populations have been unable to come to terms with each other ever since the 1974 Turkish intervention, which aimed to prevent a change in its political status quo following the Greek Cypriot military coup against the internationally-recognised government of the Republic of Cyprus.

The guarantors of the Republic of Cyprus — Turkey, Greece and the UK — initiated a reunification plan in 2002 led by former UN secretary-general Kofi Annan. Greek Cypriots rejected reunification with Turkish Cypriots on the referendum in 2004. The European Union, which supported Greek Cypriots on the island, accepted their administration as a representative of the entire island and a full member of the bloc following the referendum.

With the relaunched Cyprus talks in 2015, there was hope that the newly discovered gas reserves would inspire Turkish and Greek Cypriots to address the island’s political deadlock.

But that did not happen. Following the failed UN-sponsored talks, Turkey announced that Ankara would retaliate against unilateral Cypriot Greek exploration in the region, starting its own exploration efforts in April 2017.

Turkey’s new deal with Tripoli could force other Mediterranean powers to reach out to Ankara to implement the EastMed project.

“Through this deal, we have taken a rightful step within the framework of international law against the stances imposed by Greece and the Greek Cypriot Administration, opposing the claims of maritime jurisdictions aiming to confine our country to the Gulf of Antalya,” Erdogan said.

“Our concern is not to create enemies but to make friends. If there are enemies to us, we want to offer them our friendship,” the president added.

Turkey’s Libya agreement also carries implications for the prospects of Libya’s brutal civil war, where Ankara and its Gulf ally Qatar support the Government of National Accord (GNA) while the UAE, Saudi Arabia, France and Russia back Tobruk-based rival forces led by Khalifa Haftar, a 75-year-old warlord.

The GNA governs the country’s western regions while Haftar claims most of its eastern territories.

Under Haftar’s recent assault, backed by Russian mercenaries, Tripoli mostly relied on Turkey, which indicated that if necessary Turkey will come to the aid of the GNA.

Source: TRT World